Analysing the COVID-19

disruptive impact on Montevideo’s Supply Chains

Analizando el

impacto disruptivo del COVID-19 en las cadenas de suministro de Montevideo

Matías Aresti [1], Felipe Algorta [2], Ignacio Bertoncello [3], Manuel Aramis Flores [4], Matías Crosa [5], Martin Tanco [6]

Recibido: Febrero

2022 Aceptado: Mayo 2022

Summary. - Globally,

COVID-19 reached unprecedented levels of contagion, affecting the social

meetings, public spaces, and many everyday aspects. During the first days of the

pandemic, supply chains were severely impacted by a great uncertainty in

socio-economic terms, causing irrational variations and the inability to

forecast demand. In this paper, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the

behaviour of different companies is analysed based on the variation in supply

and demand of consumer-packaged goods. The pandemic outbreak disruption, the

bullwhip effect caused by demand fluctuations, and the resilience of different

companies were studied. A multiple case study methodology is used to analyse

the decision-making process of fourteen different companies, from diverse

sectors in Uruguay, affronting the pandemic. The paper’s main findings include

the identification of disruption and operation risks along with coordination in

supply chain management during the first four months of the pandemic. Moreover,

due to the necessity of sanitation and comestibles, and the fear of stockout,

consumers’ demand was uncertain, and the bullwhip effect was observed in

critical channels of some products. Finally, the resiliency and robustness of

the affected companies were studied and good practices for a resilient and

robust response to the pandemic were identified and analysed.

Keywords: COVID-19,

Logistics Management, Supply chain resilience, Bullwhip effect.

Resumen. - Mundialmente, el COVID-19 generó niveles de contagio sin precedentes,

afectando reuniones sociales, espacios públicos, y muchos aspectos de la vida

diaria. Durante los primeros días de pandemia, cadenas de suministros fueron

afectadas debido a una gran incertidumbre de factores socioeconómicos, causando

una alta volatilidad en la demanda resultándola impredecible. Este artículo

analiza el efecto que tuvo la pandemia en el comportamiento de diferentes

empresas considerando las variaciones en la oferta y demanda de bienes de

consumo envasados. Las perturbaciones generadas por la pandemia, el efecto

látigo causado por fluctuaciones en la demanda, y la resiliencia de diferentes

empresas son estudiadas. Se utilizan múltiples estudios de caso para analizar

el proceso de toma de decisiones de catorce empresas uruguayas, de diversos

sectores, enfrentándose a la pandemia. Entre las observaciones realizadas se

destacan la identificación de riesgos operacionales y disrupciones, y una alta

coordinación en la administración de cadenas de suministro durante los primeros

meses de pandemia. Asimismo, necesidades sanitarias y alimenticias, y el miedo

al agote de stock, causaron demandas inciertas, ocasionando un efecto látigo en

ciertos canales de productos. Finalmente, la resiliencia y solidez de las

empresas es estudiada, y se identifican y analizan buenas prácticas para

afrontar la pandemia.

Palabras clave: COVID-19,

gestión logística, resiliencia de las cadenas de suministros, efecto látigo.

1. Introduction. - The

COVID-19 outbreak represents one of the major disruptions encountered during

the last decades and has drastically impacted most aspects of human activities

[1]. It has had a profound impact on supply chains [2], and its unexpected

nature has generated new trends in public behaviour, which made decision-making

processes challenging for supply chain managers. Moreover, the impact and the

duration of the pandemic were completely unpredictable [3].

Disruptive events such as the Coronavirus

pandemic can be classified using different criteria [4, 5]. In terms of the

disruption’s lead time, this crisis was rapid (little or moderate advance

notifications, present warning signs), severe considering the impact of loss

(causing a high level of economic loss and/or many deaths), and international.

Every disruption has a time component to its

effects, which is key for understanding its synergy and predicting its

consequences [4, 6]. Generally, in the very first stage, the preparation stage,

organizations can predict the event and plan operations to reduce its impact.

This is followed by the first response period, where the aim is to control the

situation, focusing on protecting lives and preventing further damage. After

this, companies start recovery preparations, notifying the rest of the supply

chain’s links and redirecting resources. Finally, when companies make up for

lost production, the recovery phase takes place, but generally, a long-term

effect will persist causing a possible improvement in performance or a negative

impact as customer relationships and trust may be damaged.

Pandemics and epidemics are a particular kind

of disruption, as they are characterized by the three following components of

threat: (1) the presence of long-term and unexpected scaling disruption, (2)

disruption propagation in the supply chain and epidemic outbreak propagation in

the population, and (3) disruptions in the development of logistics, demand,

and supply [7]. In contrast to most disruption threats and risks, epidemic

outbreaks are minor at the outset and infrastructural impact, but they develop

and spread over various geographic areas rapidly. The latest pertinent examples

include the MERS virus, SARS virus, Swine flu, Ebola, and the most recent one,

COVID-19.

In this research, the effect of the COVID-19

pandemic on the behaviour of different retail and logistics companies was

analysed based on the variation in supply and demand specifically in

consumer-packaged goods (CPGs). The occurrence of a supply and demand imbalance

caused by a major disruption is assessed using a multiple case study

methodology, aiming to also identify the potential materialization of the

bullwhip effect in the companies that participated in this study. Different

actors along the supply chain were interviewed at two different stages of the

pandemic to analyse behaviour while the pandemic effects were shifting. In

addition, this paper also aims to identify the different risk management

decisions taken to affront the pandemic to determine managerial tendencies in

terms of logistics and product distribution in such a scenario.

The opportunity to evaluate this phenomenon in the Uruguayan context is

key to this analysis, as contagion curves and public policies differed quite

notably compared to most countries in the region, mainly in the first months of

the pandemic. The government appealed to the social responsibility of citizens,

and the mandatory confinement measure was not taken. These decisions, added to

aggressive testing (1610 tests per new case in June 2020) and rigorous

identification and monitoring of sources of contagion, resulted in the correct

management and response to the pandemic [8].

The article is structured as follows. Section 2

presents a literature review in the fields of disruptive events that impact

supply chains, causes and consequences of the bullwhip effect, and resiliency

in supply chains. Section 3 outlines the research methodology used for this

study. The results and discussion are presented in Section 4, followed by the

main research conclusions in Section 5.

2. Literature

review. -

2.1. Supply chain visibility

and bullwhip effect. - Disruptions will, in all likelihood,

cause some sort of effect either in consumer behaviour or in the ability of

different parts of the supply chain to provide goods or both. A common issue

with supply chains is the poor visibility upstream and downstream from a

particular link in the chain [9]. Distorted information between ends of supply

chains causes inefficiencies such as excessive inventory investment, poor

customer service, lost revenues, misguided capacity plans, ineffective

transportation, and a loss of effectiveness to comply with predefined

production schedules [10].

This phenomenon is widely

known as the bullwhip effect. The term was coined by Lee [10], although prior

publications already established consequences of lack of visibility and poor

demand forecasting. Forrester indicated that it is empirically recurrent that

the variance of perceived demand to the manufacturer far exceeds the variance

of consumer demand, and the effects of not being able to accurately forecast

needs from intermediate players in the supply chain, as they relate to actual

customer demand, are observed to be larger for manufacturers than for retailers

[11]. In other words, the lack of visibility between participants in a supply

chain causes minor shifts in consumer demand to result in large variations in the

size of the orders that reach the manufacturers upstream in the supply chain

[10, 12].

The bullwhip effect can be

caused by several factors. One is demand forecast updating. Forecasting is a

decision-making process that is frequently used in every link of the supply

chain to predict what the demand for products will be. The combination of

inconsistent demand signals, due to different disruptions such as price

fluctuation or natural disasters, and forecast-driven organizations that make

isolated decisions along the supply chain, causes the real demand to be

amplified increasingly as it moves upwards [9].

The demand forecast updating

falls into another reason why the bullwhip effect occurs: the lack of

communication. Misinformation both inside or outside an organization is

reflected in large time lags between reception and transmission of information

and deliberates into excessive inventory [11, 13]. Ultimately, the effect

consists of a real fluctuation in demand which triggers a forecast-driven response

in the last link of the supply chain followed by a forecast-driven response of

the second link based on the former forecast and so on. The effect will be

aggravated by anything that decreases forecast precision, such as long lead

times, or lack of communication with the extreme case being decision-makers

relying only on adjacent links’ information.

Moreover, order batching is an

additional factor that magnifies the bullwhip effect. There are two ways of

order batching: periodic ordering, in which an order is placed after a specific

period (weekly, monthly, etc), or push ordering, in which the products are

ordered prematurely expecting to modify or affect the customers’ behaviour

[10]. The batching of orders induces demand variance up the supply chain that

is not present at lower levels of the chain. Furthermore, order batching can

delay orders and thus hinder information flow throughout the supply chain

making them less responsive [11].

Rationing and shortage gaming

is a managerial resource when demand exceeds supply. If there are not enough

products to satisfy customers’ requirements, fractioning the number of products

available is an existing alternative. In this case, the customers’ orders will

be excessive in reaction to this shortage and may not reflect the product’s

real demand to the manufacturer, leading to the bullwhip effect [10].

A system must be well prepared

to cope with these imbalances to ensure continued operation and to survive in a

world in which supply chains extend throughout the globe [14].

2.2 Supply chain risk management. - To mitigate the

disruptions´ effects, or avoid them altogether, supply chain risk management

(SCRM) comes into play. SCRM can be defined as ‘‘the management of supply chain

risks through coordination or collaboration among the supply chain partners to

ensure profitability and continuity’’ [15]. For industries that are moving

towards longer and more interconnected supply chains (e.g., outsourcing) and

facing an increasingly uncertain demand and supply, risk management is vital.

As supply chains go leaner and more integrated, it is more probable that

accidents in one link of the chain affect the others [16].

The SCRM consists of four key

stages: risk identification, assessment, treatment, and monitoring. These four

stages are developed by the internal implementation of tools, techniques, and

strategies. It also consists of external

coordination and collaboration with supply chain members to reduce

vulnerability and ensure continuity coupled with profitability, leading to a

competitive advantage in adverse situations [17].

2.3 Resilience in supply chains. - Disruptive events

and the materialization of the bullwhip effect can directly affect the ordinary

activity of companies. External shocks to supply chains that are not optimized

to mitigate these situations can cause disruptions that are several orders of

magnitude larger than the disruption itself. The resilience of a supply chain

can be considered as “its ability to reduce the probabilities of facing a disruption,

the consequences of those disruptions once they occur, and the time to recover

normal performance” [18]. An additional concept that refers to the adaptability

of a supply chain is robustness. Robustness is the ability to continue with

operations and to maintain the level of service while sailing through internal

or external disruptions [19].

Once a disruption has

occurred, the primary source of uncertainty for managers is the demand for

products. Hence, the ability to respond to the variability of the demand in

disruptive events is tightly associated with resilience [6]. Three kinds of

capabilities can lead organizations to be resilient: (1) flexibility, which

refers to a quick ability to evaluate and take needs into account responding to

end consumers; (2) integration capabilities, which refer to the degree to which

a manufacturer strategically collaborates with its supply chain partners and

collaboratively manages intra and inter-organizational processes and (3)

external capabilities that relate to the collaboration through systems such as

Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) and Collaborative, Planning, Forecasting, and

Replenishment (CPFR) with retailers to enhance close cooperation among

autonomous organizations engaged in joint efforts to effectively meet

end-customer needs [20].

When talking about resilience

and robustness of supply chains, it is assumed that the ability to manage risk

and to take accurate decisions leads to a better positioning vis a vis

competitor to deal with disruptions and, also, to try to take advantage of the

adverse situation, to act as a potential source of competitive advantage [21]. In particular, having a vast range of suppliers and

preventing or avoiding risks were identified as vital factors to ensure

resilience [22].

The planning decisions taken

under the demand uncertainty of a supply chain caused by a specific disruption

are fundamentally taken to maximize its economic performance. Planning

decisions are related to the determination of production rates, inventory levels,

forward and reverse flow amounts, and transportation links. These decisions

involve actors such as consumers, supermarkets, stores, offices, distribution

centres, and factories. In that way, both resilient freight transportation and

an effective communication system are critical to standing against disruptions

[23, 24, 25].

Moreover, when facing a

pandemic situation, the daily monitoring of global suppliers plays an important

role due to the perceived fluctuations and the demand uncertainty. New

technologies, such as artificial intelligence and natural-language processing,

permit extensive supplier monitoring [26].

2.4 Research gap. - With the world facing the

COVID-19 pandemic, an opportunity is presented to analyse the effects of

disruption with a scale and reach that has not occurred in the era of

globalized global spanning supply chains. This setting is putting enormous

pressure on supply chain managers to cope with demand and supply for their

companies to be able to survive the disruption in the best way possible. The

deep implications of the decisions being made by governments and the

uncertainty of the duration of the disruption call for analysis of the effects

that supply chains are suffering and what they are doing and planning to do in

the future.

Even though there have been

worldwide pandemic disruptions in recent decades, none of them has had such a

high score both in transmutability and clinical severity as the COVID-19

pandemic when measured with the Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework. For a

similar event in severity, we need to reach as far back as 1918 for the Spanish

flu pandemic [27]. The world has changed immensely since then, and thus

research regarding the situation is valuable.

Moreover, studying the phenomenon

in Uruguay is a unique opportunity to study the influence of demand’s behaviour

and economic shock impact on the reactions of supply chains and their

resiliency in a developing country. Valuable information could be obtained to

identify strengths and weaknesses displayed by the supply chains as well as to

evaluate different measures and decisions made during the first months of the

COVID-19 disruption.

3 Methodology. - A multiple case study was

undertaken to analyse the impact caused by the COVID-19 on Montevideo´s supply

chains during the first four months of the pandemic. To understand the

decisions that relevant retail and logistics´ actors had taken, and to

understand the reasons for their attitudes and opinions, it was necessary to

carry out a qualitative analysis [28]. As the event of the global pandemic had

no previous precedent and the entire world was affected, new problems and

conflictive situations appeared daily. To face this phenomenon, managers had to

constantly make decisions to respond to the fluctuating demand of the market

and the unexpected changing in policies and lockdowns. In this case, it was

considered relevant to cover contextual conditions by the establishment of

personal contact as it was considered strongly pertinent to the phenomenon of

study [28, 29].

There are three different

methodological approaches to case research: theory generation, theory testing,

and theory elaboration [30]. This study was conducted through theory testing.

It was expected, for example, that the supply and demand of some specific

products responded to the bullwhip effect and, therefore, the different actors

within the supply chain would react in consequence. In theory-testing case

research, the general theory is contextualized before subjecting it to the

empirical test. Moreover, the case study propositions come situationally

grounded already in the theory phase of research [30].

For case studies, theory

development as part of the design phase is essential, whether the ensuing case

study’s purpose is to develop or test theory [29]. The case study of the

COVID-19 situation is classified as embedded (multiple units of analysis) and

multiple-case design because multiple periods (different contexts) and several

cases within each period (different companies) were considered to observe

several measures and reactions to the affronted crisis.

Regarding the construction of

the interviews, the scope of the interviews was defined first, and the theory

was developed to gather valid and reliable data relevant to the research [28].

The research aimed to study the effect of COVID-19 on the behaviour of

different production, distribution, and wholesale companies in Uruguay. In this

line, the objective of undertaking interviews was to observe and understand the

reactions and decisions taken by the operation and logistic managers due to the

pandemic situation.

In this way, it was decided to

complete two rounds of interviews to study the supply chain reactions to the

pandemic at different stages of the global disease in the country. The first

round of interviews was executed in March 2020, within the first four weeks of

the arrival of the pandemic in Uruguay, to observe and study the first supply

chain reactions. The second round was performed during the third and fourth months

after the first COVID-19 case in Uruguay was diagnosed. This round of

interviews allowed us to analyse the situation in a clearer and more stable

context regarding the pandemic.

The theory to prove considered

three points to analyse. In the first place, the influence of the pandemic

outbreaks leading to important disruptions in terms of the presence of

long-term and unexpected scaling disruption, propagation of the virus in the

population, and disruptions in the development of logistics, demand and supply

was studied. Secondly, these affectations were deepened to observe the

variations in the consumer’s behaviour due to the pandemic and how those

variations lead to diminishing the businesses’ visibility disemboguing in a

bullwhip effect situation. Thirdly, the capacity of businesses to be resilient

and the importance of coordination among the supply chain to succeed were

tested.

Furthermore, both interviews

were designed to test the theory. There are different kinds of qualitative

research strategies and they can be classified by the type of questions being

asked. Generally, what questions may either be exploratory or about prevalence,

in which surveys or the analysis of archival records would be favoured.

Moreover, how and why questions are likely to favour the use of case studies,

experiments, or histories [29]. In the case of the impact caused by COVID-19,

it is relevant to observe businesses’ reactions and behaviour. In this way, it

is relevant to ask what, how, and why questions. The framework and the

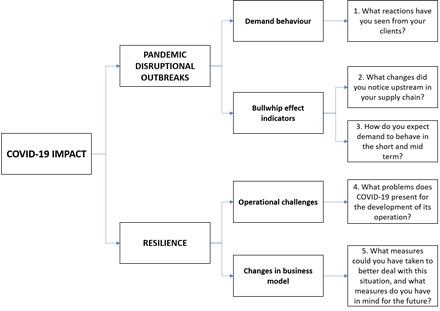

questions asked in the interviews are presented in Figure I.

|

|

|

Figure I -

1st round Interview framework |

In terms of the execution, the

first round of interviews was completed in the first four weeks of the COVID-19

pandemic. Fourteen managers of fourteen different organizations from the CPGs

channels of foods, pharmaceuticals, personal hygiene products and fashion were

included in the study. The set of interviewed businesses ranges from

manufacturing to transportation service companies.

|

||||||||||||||

|

Table I -

Number of managers interviewed by business area |

Once the interviews were fully

transcribed, the mass of qualitative data collected was structured into

meaningful and related patterns or categories to explore and analyse the data

systematically and rigorously. Interpreting qualitative information is, to a

great extent, a challenge in making sense of chaos. A useful technique to see

an order from chaos involves structuring the data in a variety of patterns [28,

31]. The generated coding structure is stated in Table II.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table II –

Coding structure |

The template analysis involved

categorizing and unitizing data. The information was coded and analysed to

identify and explore themes, patterns, and relationships. The template approach

allowed codes and categories to be shown hierarchically to help the analytical

process. The process of analysing interview transcripts or observation notes

led to some of the codes being revised and even changes to their place or level

in the template hierarchy. [28]. After the execution of the first round of

interviews, the pandemic situation began to stabilize in Montevideo and the

second round of interviews was designed.

The questions included in the

second round were adapted to observe the behaviour of the supply chain, making

the focus on those points identified after the first round of interviews. The

execution of the second round of interviews was completed in the third and

fourth months after the diagnosis of Uruguay’s patient zero. The same fourteen

actors from the specific CPGs channels of foods, pharmaceuticals, personal

hygiene products, and fashion were contacted. However, one of the actors was

impossible to contact and, finally, the second batch consisted of thirteen

interviews.

Once the second batch of

interviews was fully transcribed, the mass of qualitative data collected was

structured and analysed. The same framework utilized for the first round of

interviews was used to develop the coding structure and to analyse the results

of the second round.

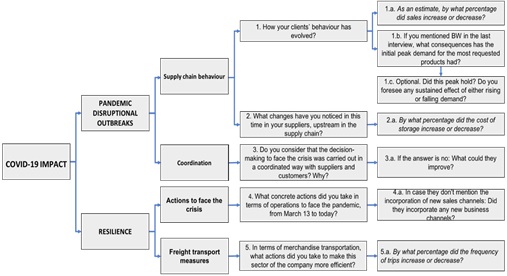

|

|

|

Figure II

– 2nd round Interview framework |

4 Results and Discussion. - On the demand end

of the supply chain, a shock in demand caused by fright buying was initially

observed. According to one of the interviewees, in the first days of the

pandemic “the reaction was panic, due to the situation of a possible

quarantine. This automatically led to a substantial increase in the demand for

CPGs”. This in turn put supply chains relying on “Just in Time” methodologies

under considerable pressure and the sight of empty shelves became normal.

4.1 Pandemic outbreak disruption. - In terms of

disruption risks caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, one of the main problems

observed was the difficulty in accurately forecasting the consumers’ behaviour

in the first weeks of the pandemic [1]. This forecasting problem turned into

uncertainty about the demand´s behaviour, which restricted management’s

capacity to make operational decisions to accurately balance supply and demand.

The principal difficulty to

forecast the consumers’ behaviour lay in the irrational consumer behaviour

during the initial moments of the pandemic. One of the interviewees mentioned

that during the first pandemic days: “We have very unstable demand parameters

and that makes planning substantially difficult since it is not possible to

determine what was going to be delivered the next day. The level of demand

observed these days is not normal and it is changing day by day, so we must

adapt daily to meet delivery orders”.

This was reflected in specific

peaks of consumption, especially in CPGs and personal care products, to avoid

potential shortages of items perceived to be of first need. Although in Uruguay

the COVID-19 outbreak was not so critical during the first months compared to

other countries, the first social reaction was panic, because of the

possibility of a national quarantine status, which automatically lead to a

substantial increase in the demand for CPGs and personal care products. In the

second round of interviews, it was perceived that the demand stabilized.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table III

- Pandemic outbreak disruptions interview coding |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

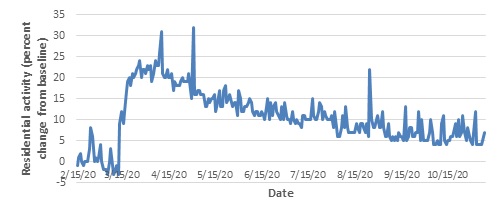

Faced with the unexpected and

constantly changing demand situation, companies engaged in manufacturing,

import, and distribution of goods commented to have experienced a

"survival" mode to meet the operational needs. One of the main

difficulties was the migration of consumers to residential areas and the

problem of the general decrease in economic activity. Even though there was not

a strict quarantine declaration in Uruguay, the government strongly encouraged

citizens to remain in their houses. This governmental recommendation had an

impact on the migration of the population’s activity to residential areas.

This measure impacted

negatively on the businesses located in centric and working areas, as fewer

customers frequented their stores, and some of them had to close entirely,

either temporally or definitively. One of the interviewees contributed: “The

activity varied according to the area of the city, given that in residential

neighbourhoods the activity increased. In downtown areas where there is a

concentration of offices and public spaces where social activity fell, a

consequent drop in merchandise distribution was observed, unlike in residential

neighbourhoods”.

Department stores and

supermarkets located in residential areas perceived an uprise in their demand,

as customers visited the stores more frequently, and bought higher volumes per

visit. The supermarket chain operations manager stated: “It was a sudden change

from one day to the next. Of course, some products were stocked out, not

because there were problems in the supply channel, but because the demand

doubled from one day to the next. The first weeks were chaotic, fights were

detected over certain products in stores”.

|

|

|

Figure III

- Social behaviour in Montevideo (Source: Google LLC "Google COVID-19

Community Mobility Reports”) |

In terms of perception of a

general decrease in economic activity, except for some specific product

channels, a general decrease in demand was noticed. The main causes of this

decline were the migration of consumers toward essential and basic products and

the reduction of people's purchasing ability due to the crisis. As months went

by, the loss of income for the average consumer became clear. The interviewees

mentioned that a considerable drop was noted in the level of sales.

Moreover, distribution was

strongly affected by the drop in the activity of micro, small and medium

enterprises (MSMEs) which represented a significant percentage of the customers

of the logistics companies that participated in the study. MSMEs were the

businesses that were hit particularly hard by the pandemic, due to their

reduced scale and low capacity to adapt to abrupt changes. To some extent,

MSMEs experienced a reduction in the supply of labour, their ability to

function was constrained and they experienced severe liquidity shortages due to

a dramatic and sudden loss of demand and revenue [3]. Despite the sudden

increase in the volume ordered by supermarket chains during the first weeks,

the MSMEs’ situation impacted directly the reduction

of general supply activity.

Lastly, retailers tended to

ask for higher credits from wholesalers, caused by uncertainty of the

significant slump in the customers’ revenues caused by the pandemic, which

resulted in an important delay of the payments cycle. This condition augmented the difficulty to

manage the company and increased the risk of going bankrupt, causing a

considerable amount of businesses to close their

doors.

Overall, the principal

disruption risks observed were difficult to forecast demand during the first

weeks of the pandemic which turned into uncertainty about the demand´s

behaviour and restricted management’s capacity to make operational decisions.

The situation stabilized and in the second round of interviews, this disruption

risk was not mentioned.

The main cause of the

difficulty to forecast demand was the irrational consumer behaviour during the

initial moments of the pandemic. This irrational consumers’ attitude was

specifically spotted during the first weeks of the pandemic. In the second

round of interviews, the observed “new normality” caused changes in customers’

behaviour, yet explainable and manageable when making decisions within the

supply chain.

In addition, a decrease in the

general economic activity was attributed by the interviewees to the migration

of consumers towards essential and basic products, and the reduction of

people's purchasing ability due to the crisis. The contacted companies’ sales

levels, although they increased in some specific sectors such as essential

products that refer to personal care and hygiene according to the pandemic,

generally dropped.

Operational risks were mainly

related to the adoption of operational changes to adjust to the COVID-19

situation. Public health measures such as self-isolation and movement

restrictions in addition to actual COVID-19 cases among the workforce posed an

uncertain scenario not only for manufacturers but also for transportation and

distribution networks. Extra resources have been put in place to implement

contingency plans to mitigate risks. Furthermore, international trade has been

affected by “thicker borders” [32], impacting all products that have imported

components.

All running businesses had to

implement personal protection measures to make sure their workers and customers

were safe to continue operating. Specific actions such as adaptation of the

work shifts, spacious workplaces, providing workers with facemasks, gloves,

sanitiser, sanitation spots with soap to wash their hands, training sessions to

understand the seriousness of the matter, and contingency plans in case of

contagion were undertaken. Another action taken to reduce contact was to carry

out remote selling and avoid visiting customers.

This adoption of specific

measures taken to guarantee personal protection was highly mentioned in both

rounds of interviews. Moreover, in the second round of interviews, in which the

demand situation and production and logistics activities had stabilized, it can be seen that the sanitary and protection measures

embraced were, in some way, motivators of such stability.

Furthermore, personnel and

workload shortcuts were identified as operational risks. The decrease in

general demand, and the financial hit caused by the crisis, lead to an

important reduction in working activity. In this aspect, some companies decided

to reduce the personnel and the workload. For example, numerous companies were

affected directly by the decrease in the sales capacity, leading to a reduction

in the company’s structure in the commercial sector. At the operations level,

some had to reduce personnel to lessen the preparation and delivery capacity.

Finally, at the administrative level, the same happened. The general reduction

of the economic activity generated reductions in the companies’ structures in

terms of personnel and time.

Finally, to stand against the

suffered crisis, the coordination between the supply chain actors is considered

substantial. Even though uncertainty levels were high in the first weeks of the

outbreak, and no prediction of the near future could be made, many companies

made decisions without sufficient coordination among other impacted links of

the supply chain. For example, due to the excessive demand for sanitation

products, imported product flow was shortened as external companies

strategically decided to supply their country’s demand and reduce product

export. In one of the interviews, it was mentioned that during the first

moments it was difficult to coordinate within the supply chain not because

there was no communication, but because of the level of uncertainty at hand.

Moreover, the pandemic

situation caused a global impact and all the links in the supply chain were

aware of it. Some of the interviewees mentioned that there was more

coordination now than before the pandemic, as it favoured the growth of

communication. One of the managers from a food distributor commented that they

had the objective to not cut the food supply. To guarantee the delivery and

service with the suppliers that the communication presented a greater

complexity, a more intensive communication was used: “For the links that are

more resistant to communication, our team was in charge of frequently

contacting the different managers to generate that flow of information”.

One of the interviewees

catalogued the COVID-19 as a new problem that was summed to the habitual

problems in supply themes: “We have an effective communication system

regardless of this specific topic: COVID-19. This is one more issue that adds

to the usual ones, there will always be problems to solve”.

The pandemic was an

opportunity for some companies to work collaboratively. In general terms, in

the first round of interviews, it was observed that collaboration between the

different links of the supply chain was scarce. However, in the second round of

interviews, a higher level of coordination upstream and downstream in the

supply chain was mentioned.

4.2 Bullwhip effect. - Some specific sectors

experienced an exponential rise in demand that led to shortages and the

necessity to take important decisions to adapt their distribution plans. The

main sectors that perceived an increase in demand in the first weeks of the

pandemic were cleaning, personal hygiene, and food products. This increase was

attributed to the declared sanitary emergency by the government, to the

motivation to adopt personal care measures due to the ease of contagion

presented by the virus, and finally to the imminent threat of compulsory

lockdown.

A misperception of excessive

demand increase was perceived by suppliers, which was caused by this sharp and

sudden upgrowth in demand on the side of retailers (and a consequent placement

of excessive orders to suppliers), together with the buyer's tendency to

over-supply in anticipation of a possible total quarantine. This tendency, known

as panic buying [33], distorts suppliers´ demand perception, is frequently

observed in disruptions and natural disasters, and causes inventory struggles.

According to literature, this

phenomenon is called the bullwhip effect and it can lead to severe consequences

for the businesses’ development in terms of inventory, operations, and

logistics management [12]. One of the interviewees mentioned that a sudden peak

in demand was perceived, especially in the area of personal care and household

hygiene products. The first fifteen days were complex in aligning demand with

capabilities and the demand exceeded the capacity several times.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table IV -

Bullwhip effect interview coding |

|||||||||||||||||||||

The factories, importers, and

wholesale companies that took part in the study mentioned that, during the

first fifteen days of the pandemic, they did not have real visibility of

end-customer demand, but an exaggerated version produced by their downstream

customers. The shortage of customers and the consequently reduced sales paired

with the erratic behaviour of participants in the supply chain led to highly

variable production schemes in factories and high inventory costs. In terms of

personal care, household hygiene, and some essential food products the bullwhip

effect was definitively observed, and the different companies had to adapt and

respond to a variable and unexpected demand.

An example of this phenomenon

could be seen in one of the interviews with a manager of a bathroom tissue

factory at the beginning of this pandemic. Toilet tissue, being a product with a

low price-to-volume ratio causes merchants generally not to hold large

inventories, and the supply chain tends to be tight and efficient. When the

first cases of COVID-19 appeared in Uruguay, the demand exceeded the production

found in the stocks of the selling companies, even though the physiological

needs of the people did not change due to the pandemic.

The increase in demand for

household products was almost instantaneous, and the shortage of stores caused

the public to over-supply. This peak in demand caused retailers and

distributors to demand a significantly larger stock of inventory than usual. In

response, the factory ceased to produce a wide range of products and focused

instead its production schemes towards the most demanded products.

However, the increase in

demand for these specific items did not continue indefinitely. These peaks were

clear in the second half of March and some localized peaks in April, causing

stock problems as the industry was not prepared to supply the present demand.

Another effect that allows

determining that the bullwhip effect occurred was the human feelings being

involved in decision-making processes [10]. The shocking situation caused fear

and desperation in society, mainly associated with the fact that there was no

historical record of such a global pandemic, and it was impossible to predict

the progress of contagion. These feelings, when present in decisions, distort

real demand numbers and snowball through the supply chain causing inventory

struggles and misuse of production capacities. In the first round of

interviews, it was said that this kind of crisis generates nervousness in all

areas, causing excessive decision-making or a lack of prudence in situations of

tension.

In terms of the consequences

of the bullwhip effect, the breach of orders and the portfolio reduction, which

are considered consequences of the bullwhip effect [10], were identified.

As retailers perceived an

extremely high demand in an exceedingly short time, they had to prioritize

clients and concentrate on certain channels to supply these regularly.

Companies that delivered healthcare products and basic foods experienced an

extremely high demand in a short time, for which they had to prioritize clients

and channels, to define whom to deliver to supply all channels as far as

possible.

Regarding portfolio reduction,

some companies generated a list of a few dozen critical articles that strictly

have to do with the needs related to the COVID-19. Other companies reduced

their products catalogue and adopted a push selling strategy with the remaining

products. For instance, one of the interviewees mentioned that they “went from

forty-four to less than half of the product codes, and sales are being

concentrated on those products, guiding customers to buy those specific

products”.

To sum up, the bullwhip effect

was identified during the first four weeks after the first COVID-19 case in

Uruguay, and consequences were perceived. Low visibility of demand, changes in

consumption, and the influence of human feelings in critical situations were

observed. The product brunches that suffered the bullwhip effect were personal

care and household hygiene and basic foods. According to the interviewees,

these kinds of products were considered indispensable by customers to overcome

the pandemic and, consequently, people overstocked, leading companies to

struggle against shortages and excessive orders.

4.3 Resilience. - Finally, in terms of

resilience and robustness in the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, three

important aspects were assessed: the importance of a resilient supply chain to

respond to the crisis, actions to adapt and take advantage of the crisis, and

the benefits of having a resilient freight transportation link [19, 22].

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table V –

Resilience interview coding |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Resilience and robustness were

critical characteristics that organizations had to show to survive and even

take advantage of this crisis. Particularly, having a vast range of suppliers

and preventing or avoiding risks were identified by interviewees in both rounds

of interviews as vital factors to ensure resilience. One of the interviewees

mentioned in both rounds of interviews that the benefit of having a variety of

strong suppliers in different product channels resides in the fact that, in

case of disruptions, some of them may fall, but others will stand or grow and

stabilize the economic activity of the business.

Furthermore, developing risk

mitigation plans such as considering local suppliers (higher costs but lower

lead times) and investing in online channels were remarked prevention

strategies to affront the crisis between the interviewed companies.

To evaluate resilience, the

actions taken to adapt and take advantage of the crisis were analysed. The most

frequent action was the decision to diversify sales channels. Due to the

reduction in commercial activity, companies were forced to adopt new

distribution and commercial practices. For instance, a vast number of

businesses started or accelerated their development on delivery or non-personal

channels, to avoid contact and possible contagion or to gain access to clients

that migrated to residential areas [34].

One of the interviewees

noticed that: “We migrate to the use of the website, the generation of product

baskets, to that type of variants that allow us to reach the final consumer

which we cannot reach by other means”. The interviewed companies migrated to familiar

formats and product baskets and the e-commerce channel. According to one of the

interviewees “the e-commerce channel was substantially enhanced. What had grown

in 3 or 4 years, doubled in 2 months”.

Furthermore, another

observation from the interviews was the influence of governmental

recommendations on business decision-making. In the case of Uruguay, the

government proposed a new format of partial unemployment insurance and some

companies decided to follow this proposal so as not to fire people or send full

unemployment insurance. Being COVID-19 a national emergency, the government’s

proposals to return, step by step, to normality turned into a considerable

point to take decisions and design plans to face the pandemic.

Another noted action was the

improvement of the existing service due to the demand decrease. One of the

interviewees commented that “to the extent that we have fewer delivery points

we have improved the service as much as possible in some way given that there

is a competition to win. Also, there is a service to provide the essential

products at the right time and place, it is not only a business issue but a

critical social issue”.

In terms of the import of

goods, the complexity of this activity increased due to the border restrictions

with neighbouring countries. Uruguay is highly dependent on activity in Brazil

and Argentina since many products are manufactured there, so border closure and

reduction of working hours in neighbouring countries directly affected local

supply chains.

The fact that the Uruguayan

market is smaller than other countries in the region also has an influence, so

importers cannot be as demanding in terms of the volume of orders. In this

scenery, to reduce the risk of shortages, many companies, mainly manufacturers

and distributors, turned to local suppliers as a strategic measure, even when

the prices offered were not as competitive as international ones. This change

of suppliers towards locals, although it normally increases the manufacturing

cost, allows to shorten production and delivery times, and therefore become

more sensitive to respond to the changes in demand.

It was observed that in the

first round of interviews, during the first fifteen days of the pandemic in

Uruguay, the low visibility and the impossibility to

foretell the demand enforced the resiliency of the different companies to

endure the pandemic crisis and uncertainty. This enforcement motivated

resilient and robust decisions that permitted the different companies to put up

with the controversial situation and to develop new business channels.

Finally, regarding the

benefits of having a resilient urban distribution, two phenomena were observed.

In the first place, some companies commented on the actions taken to optimize

the distribution fleet frequencies. A reduction in the truck frequencies was

observed, to adjust cargo and take full advantage of the available capacity per

truck in the transportation of products. During the first round of interviews,

it was noted that the way to respond to the decrease of the goods and lumps to

deliver was to unify deliveries, reducing the frequency of vehicles. Throughout

those first days, part of the transport staff did not go out on the street.

Moreover, the issue of all

precautions both in the delivery and in the handling of goods was identified in

the interviews. This protocolary delivery activity meant that at many points

the delivery has been slowed down. One of the interviewees mentioned: “in some

sectors, if you did 10-12 deliveries on the day, today you do 8. The trucks are

forced to stop further away because businesses do not receive the invoice and

do not allow the unloading of merchandise until the previous supplier has

finished their unloading work”.

On the other hand, measures to

adapt the logistic activity to new sales channels were identified, particularly

in the remote or online channel. One of the interviewees highlighted the

necessity to have a much more efficient web order logistics, constantly

adapting to customers’ behaviour and evaluating the level of service that is

expected. “We first looked for transportation to be effective to respond to our

perceived need, and transportation was effective but very inefficient. Next, an

attempt was made to improve efficiency by controlling the number of carriers,

working hours, and task management, thus adjusting the transport price ratios

about sales”.

5. Conclusions. - The Coronavirus outbreak

impacted deeply supply chains, and its disruptive nature made managerial

decision-making challenging. During the first four months since the first

COVID-19 case was identified in Uruguay, it is possible to conclude, in the

first place, that the outbreak seriously affected the structure dimension and

the operations of supply chains during the first stages of chaos and

uncertainty. The high level of uncertainty generated in the first period of the

pandemic, causing struggle to predict consumers’ behaviour, made it essential

for supply chains to enhance coordination between links, work on improving

resilience and manage risks to reduce their impact and, in some cases, even

take advantage of this crisis.

Particularly, the difficulty

to forecast demand during the first weeks of the pandemic was perceived, which

turned into uncertainty about the demand´s behaviour and restricted

management’s capacity to make operational decisions during those first two

weeks. Moreover, the irrational consumer behaviour during the initial moments

of the pandemic and the migration of consumers to residential areas were

observed. In this controversial situation, businesses had to adapt and respond

to overpass the pandemic situation.

In the period time studied, a

decrease in the general economic activity was observed. According to the

interviewees, it was attributed to the migration of consumers towards essential

and basic products and the reduction of people's purchasing ability due to the

crisis. The contacted companies’ sales levels, although they increased in some

specific sectors such as essential products that refer to personal care and

hygiene according to the pandemic, generally dropped.

Several procedures to manage

the identified risks due to the pandemic were implemented in the different

interviewed companies. For instance, the adoption of personal protection

measures and the reduction of staff and working hours were identified as a

response to operational risks and were implemented to maintain production and

transportation services active.

Moreover, the bullwhip effect

was present in some critical channels of products, such as personal care and

hygiene, and essential foods. Such a sudden peak of demand caused by both an

objective necessity of sanitation or food provision, and a subjective feeling

of panic or fear of stockout delivered important shortcut situations and came

along with modifications at the placed orders to respond in a certain way to an

unknown and variable demand. Furthermore, impacted supply chains had to enhance

communication and visibility and, in some cases, reduce the product portfolio

to avoid stockouts.

This disruptive event also

showed supply chains how important resiliency is to adapt to the crisis and get

through it in the best possible way. A survival attitude, understood as taking

important day-by-day decisions during the first weeks of the pandemic, was a

must. Also, some of the companies modified their sales channels to adapt to the

new normality. In particular, the online channel experienced an interesting

increase during the crisis, and some of the companies started to develop this

commercial method or improved their past experiences with online sales. In a

way, this can lay the foundations for the establishment of e-commerce as a

strong sales channel.

All in all, it is essential to

highlight the importance of incorporating the concepts of risk management,

resilience, and robustness into day-to-day operations to face the different

problems occurring daily in supply chain management. This research provides

deep insights observed in the first months of this disruption and offers

companies considerations to bear in mind when making decisions within this kind

of event. In that way, it would be possible to face adverse situations in a

coordinated and effective way, along the supply chain to respond to demand

fluctuations.

This study is limited

principally by the time-lapse in which the interviews were developed and by the

constrained number of interviewed businesses. It may not be fully

representative of the global situation of the COVID-19, but it may apply to

developing countries in which the pandemic was successfully controlled and in

which the mandatory quarantine was not established.

Further research about risk

management, resilience, and robustness of the supply chain should be carried out

on understanding good practices and effective strategies to respond to the

pandemic. The concept of success in terms of businesses overcoming this

disruption is directly linked to sustainability and resilience, so time has to

pass to see clearer successful measures. As it is a unique pandemic situation,

which had no registered precedents, it is fundamental to generate scientific

knowledge on how to respond to future similar scenarios in case they exist.